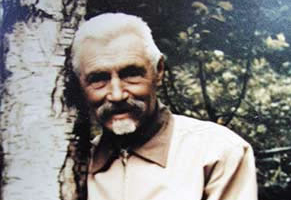

Alexander Zuckerberg Biography

Alexander Zuckerberg 1880 – 1961

The phrase ‘continue his life’ was intentionally chosen. Zuckerberg did not start over again, nor did he become someone new when he came to Canada. He brought with him all that he was, knew, and experienced while in Russia, and he carried it on in this country. Perhaps that is part of the mystery that surrounds Zuckerberg even today. When Zuckerberg arrived in Castlegar, he was a man fully developed, in body and soul. In order for his friends and neighbours to understand him, they would have had to understand all that had gone before. But Zuckerberg shared the greater part of himself with only a very few of his closest friends. The rest he was content to leave with more questions than answers.

This paper may not satisfy every query nor cover every aspect of Zuckerberg’s complex life, but it will clarify a number of the speculations and misunderstandings that have accumulated over the years.

Alexander Fedorovich Zuckerberg was born in Smorodovnik, Estonia, to parents of German descent, on November 26, 1880. He was part of a family that included two sisters and one brother. Zuckerberg’s parents later moved to Russia near the town of Velikiye Luik, where a large family estate was situated. Zuckerberg’s grandparents also lived there, as did anywhere from ten to twelve families living and working on the estate as tenant farmers.

Zuckerberg spent all his time on the estate until he left for university. His parents being people of some means, and himself showing a great aptitude for mathematics, they were able to send young Alexander to university. This was during a time when only wealth or intelligence qualified prospective students for entrance. In 1899 when Zuckerberg was only 18 years of age, he left home for St. Petersburg to attend the Institute of Technology. On the 31st of May 1903 he graduated with a degree in engineering. This degree entitled him to design factory and foundry structures, with their related buildings, and to do building-works projects under the supervision of the Public Works Minister. Zuckerberg drew up plans for two or three Orthodox churches shortly after his graduation. However, his one ambition and passion was to educate young people. Consequently he became a school principal in his hometown of Velikiye Luik.

He was married to his first wife, Leva Bogoluski, in 1910. He took a portion of the family estate for his own after the marriage. Zuckerberg lived in Velikiye Luki during the school term, and then moved back to the estate during summer, Christmas, and Easter holidays. He often brought promising students home with him to help work on the estate and to give them further teaching.

Zuckerberg’s son, Gilbert, was born in 1911. Two years later, his wife Leva died of Pneumonia. One of Zuckerberg’s sisters assumed the care of young Gilbert until Zuckerberg remarried a few years later. His second wife, Alicia Grotto-Slapikovski, was a former student of Zuckerberg’s and sixteen years his junior. They were married in 1916, and his daughter Asta was born two years later in 1918.

In 1917, the Russian Revolution shut down the Imperial School in Velikiye Luki. Zuckerberg’s job as a teacher and principal was brought to a close. He took his family to the estate to live, being the safest place for the time. The estate itself was very close to the frontlines of the battles of World War I, and the sounds of artillery were frequently heard. Zuckerberg’s brother was forced to join him on the estate when his property was overrun. Zuckerberg, however, was not content to sit idle while events ran their course. His conviction to teach was still burning. He built a trade school on his estate for the village children at his own expense.

This love of teaching and heartfelt obligation to educate proved to be of great, albeit unforeseen, value to Zuckerberg when he applied for a visa to leave Russia. The fond memories of former students, now in positions of authority, helped to speed up the application process. Moreover, the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that people be allowed to return to their land of origin. Estonia, which was declared an independent republic after World War I, was Zuckerberg’s birthplace; hence he was justified in applying for a visa. Even so, it was over a year before he was granted a visa and allowed to leave.

One complication hindering Zuckerberg’s emigration involved the selling of his property. The new government was impeding private land sale transactions. Persons leaving Russia were allowed to take no money with them. A prospective buyer for the estate offered the solution to the problem. He suggested having his relatives in Estonia pay for the estate once Zuckerberg and his family were safely across the border. To this he agreed.

For ready money, Zuckerberg sold what he could of his household goods. He turned the cash into diamonds and gold coins and hid them in small pieces of furniture and tools. He drilled holes in each item, deposited some coins or diamonds, poured in wax to prevent rattling, then re-plugged and finished the hole. Zuckerberg’s experience and skill as a cabinetmaker stood him in good stead. Come late fall of 1920, Zuckerberg and his family began their journey.

At the border, everything was searched, including the clothes they were wearing. The whole process took the better part of a day. The only misfortune involved the mantel clock. Zuckerberg had hidden a large sum of diamonds and coins in the clock, but the border authorities would not permit its’ being taken out of the country. Perhaps, clocks were common hiding places for people to secrete money and jewels.

Eventually the inspection was concluded and the family, along with all their baggage, was loaded onto a boxcar, shunted to the Russian-Estonian border, and abandoned. The cold outside and the many rows of barbed wire only added to the tedium and uncertainty of the long wait. At last, an Estonian engine carried them to the city of Narva in Estonia. In Narva, an official greeted the family with a welcome to the country, and no search was made. After a medical examination, they were free to go where they chose. After turning what money he could into Estonian currency, Zuckerberg settled his family into a house-apartment. In a short space of time, he made useful contacts in Narva, and secured a job as a mathematics and physics teacher in a German private school. Although Zuckerberg could speak German, the technical terminology was new to him, and this he had to learn. During this time, Zuckerberg was still waiting for the money from the Estonian relatives for the sale of his Russian property. Very little money was ever received.

After about one year in Narva, Zuckerberg was ready to move again. His first choice was Australia, a land far from the turmoil of war and revolution, but there was not enough money for such a long trek. Canada, meanwhile, was looking for immigrants. The Canadian Pacific Railway was willing to sponsor immigrants who would work on agricultural lands. By 1923, Zuckerberg had made up his mind to leave for Canada.

A train took the family from Narva to the port city of Reval. From there, they were ferried to Helsinki. From Helsinki, they boarded a ship for England. It was a two-day trip to England on a half passenger, half cargo ship, and involved many stops along the way, including Copenhagen.

On the sixteenth of September 1923, Zuckerberg and his family docked in Hull, England. Once contact was made with the CPR, the Railway Company made all the arrangements for the trip to Canada. A train took the family to Liverpool, where they had a stopover of one month. At last, the CPR passenger ship, the SS Montcalm arrived and took the Zuckerbergs to Canada. On October tenth, 1923, they landed in Quebec City.

After a quick and easy immigration procedure, the family loaded up into a ‘colonist car’ headed for Edmonton. These wooden cars featured a heater, a place to cook meals, and seats that folded down into beds. They arrived in Edmonton at the beginning of winter. A Lutheran church found a home for the family and a job for Zuckerberg. He had previously taught himself English and could speak it reasonably well by this time. He tried threshing on a farm for a while, but it did not suit him. Tie cutting for the CPR followed, but it proved too ambitious for Zuckerberg’s small frame. Not the least of their difficulties was the extreme cold of Edmonton. None of the family members thought too highly of it. In late spring of 1924, they left Edmonton for Vancouver.

Their first home was on Seymour Street. It was quickly followed by a move to a rented house in South Vancouver on 42nd Avenue, near the Walter Moberly School. Their son, Gilbert, went to school riding the distinctive black bicycle later used by Zuckerberg in Castlegar. One more move followed, as Zuckerberg disliked renting. This move took the family to the 1700 block of Windsor Street, where he renovated a small house. Zuckerberg found a job with an office furniture manufacturer and supplier. He proved to be a very adept cabinetmaker. At the same time, Alicia was taking her training as a hairdresser.

Zuckerberg was still not happy in his South Vancouver home. Always wanting to own land, he bought a quarter section near Chase. When he found out he had no water rights for irrigation, he abandoned the project at a loss to himself and ventured further east to Revelstoke. There, Zuckerberg bought property that, today, marks the corner of Highway 1 and the main road leading to town.

At this time Zuckerberg suffered an attack of osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone and bone marrow. He therefore sold the Revelstoke property, again at a personal loss, and used the money to buy four acres in Burnaby, located off Douglas Road, along Still Creek Avenue. The following year was spent in and out of the hospital. By 1931, the doctors had advised Zuckerberg to seek a drier climate. Quite fortuitously, the Doukhobor community in Castlegar was advertising in the Vancouver papers for a schoolteacher, to teach Russian in Castlegar and the area. Zuckerberg came to Castlegar, liked it, and was invited by Peter Verigin to remain as a teacher. He stayed with various families in the community before summoning his family to join him almost a year later.

The family stayed for a few months in rooms above the Brilliant school where Zuckerberg was teaching. Their first Castlegar home was a rented house on First Street. At the same time, Zuckerberg was negotiating the purchase of the beauty parlour property on Fourth Avenue. While in the rented house, Zuckerberg built a series of market stalls, which he intended to rent out to various merchants. The scheme was not successful, however, so Zuckerberg pulled the structures down, transported the lumber to his downtown property, and built the beauty parlour from it. The family lived in the beauty parlour facilities for a number of years. The building can still be seen today at 1114 4th Avenue.

In the early 1930’s, Zuckerberg was working on his island. While negotiating for the foreshore property, Zuckerberg had seen and fallen in love with the island, and inquired about purchasing it. An exchange of letters between Victoria and Zuckerberg followed. Victoria declared that, according to their maps and surveys, no such island existed. Zuckerberg had to insist that it was really there. Finally, Victoria was convinced and decided that the island must indeed be Crown land. Zuckerberg was free to lease the island, but not to purchase it. This he did for several years. It was not until November 1949, that Zuckerberg again tried to buy the island. He had it surveyed by Boyd Affleck, at his own expense, and sent the information to Victoria. Zuckerberg became the registered owner of the island on August 6th, 1951. Zuckerberg first built the log cabin on the island before commencing work on the house. While his building projects were in progress, Zuckerberg was teaching Russian classes for the Doukhobors.

During the summer of the first year that Zuckerberg was in Castlegar, he commuted to Trail to work in an upholsterer’s shop, building and repairing furniture. When his family joined him in Castlegar, he quit the Trail job. Afterwards, whenever he was free, Zuckerberg would help a close friend, Alec Plotnikoff, in his contracting business, but this was infrequent. Between 1940 and 1942, Zuckerberg worked on the Brilliant Dam project as the carpentry shop superintendent, building the curved spillway forms.

The main object of Zuckerberg’s attention though was teaching in the Russian schools. He taught classes in many of the local Doukhobor schools. Often he would stay in one of the community homes and travel back and forth between the various settlements. Other times, he rowed from his island to Brilliant. Zuckerberg taught the Doukhobors every night after English school. The students in each settlement had classes every other night. He taught Friday evenings and Saturday mornings in the Castlegar School. Besides supplying Zuckerberg with accommodations, the community paid him a salary of $45 per month, with many gifts of food.

Zuckerberg was a devoted teacher. He loved to educate, was more than familiar with his subject matter, and was very fond of young people. In the classroom, he expected orderly and disciplined behaviour. It was a rare occasion when he had to resort to anger or force to maintain it. The class atmosphere was usually relaxed and happy. Zuckerberg inspired his students to learn. He always had time to listen and was eager to help with any problem. Most of his students recall him now with the deepest feelings of love, sincere respect, and admiration.

In dress and bearing, Zuckerberg distinguished himself in a crowd. The local community was always intrigues by this gentle, complex man with his Russian blouses, breeches, and high boots. He was a quiet man, but by no means a passive one. Even the most superficial scanning of the Village Council minutes reveals the active involvement of Zuckerberg in community activities. In 1947, he far-sightedly recommended the formation of a Town Planning Commission. In the same year, and again in 1958, under the auspices of the Castlegar School Board, Zuckerberg offered to give evening instruction in Russian. He did teach local RCMP constables the language. Often he placed advertisements, offering to tutor students privately in mathematics. In a 1948 letter to the editor, he called himself an engineer of technology. He outlined in his letter the costs for the proposed Kinnaird School, pointing out the wide divergence between his figures and the School Board’s estimate. Zuckerberg concluded with an admonition to the public, to decide for themselves. In 1952, the Village Council asked Zuckerberg to supply tentative plans for a fire hall/city hall complex, with a community hall and transportation garage.

Zuckerberg led in many public petitions. He encouraged people to petition for better water mains, improved road conditions, to oppose capital punishment, and to support other citizen’s rights. He was called upon at ratepayers meetings and PTA gatherings to give advice on many issues. His words were always careful, measured, and deserving of attention. The Bloomer Creek outfall and the question of water rights were constant causes for battle. He played an important role in settling the gas pipeline controversy.

In 1955, Zuckerberg offered to donate one-half acre of his land to the Village for a swimming pool. He was subsequently advised that the Council could not accept it. This was but one of the several unfortunate examples of short-sightedness on the Council’s part in regards to Zuckerberg’s land offers. By 1956, negotiations were again underway between Zuckerberg and Council, this time for parkland. Nothing ever came of it. The year 1958 saw renewed talks concerning the acquisition of Zuckerberg’s land for park purposes. Again, no conclusion was reached. In August of the same year, Zuckerberg offered his boat to the Village to be used as life-saving equipment, a matter of great concern to Zuckerberg. The Village felt it could not take responsibility for patrolling the banks of the Columbia River, and so refused the offer. January and March of 1959 found Zuckerberg persisting in his offer of land for a swimming pool. The issue came to a climax in May of the same year. After much discussion and public input, a conclusion was finally reached, recommending that Council turn down Zuckerberg’s offer. The Village would only accept the property with the stipulation that they would do with it what they could, when they could. Zuckerberg asked for the return of his Land Title Deed if it was not to be used. He was bitterly disappointed.

Zuckerberg’s most memorable contribution to the community was the several occasions when he saved people from drowning in the waters around his island. The immediate island area was a favourite swimming spot for the townspeople, as well as an ideal skating rink in winter. Zuckerberg himself often joined in the swimming and skating, but most often he sat and watched the children ad they played to make sure they were safe.

In September of 1955, Zuckerberg rescued a Spokane couple whose boat had capsized during an annual boating regatta. He saw them clinging to their overturned boat and rowed out to retrieve them. Upon reaching the couple, he dryly inquired whether he could be of any assistance. His offer was accepted.

The morning of July 25, 1957 saw the near drowning of seven year old Paul Cohen. Zuckerberg was seventy-six years old at the time and suffering from a heart condition when he assisted in the rescue. Just a year later, almost to the day, Bob Brandson did drown while attempting to swim across to Zuckerberg’s Island.

Sculpting was a facet of Zuckerberg that had its’ precedent in Russia. He had many busts in his home and sculptures lining the island pathways. The ‘Stump Woman’ near the house and the wooden facemask over the porch are probably his most well known works. He sculpted as a hobby for enjoyment and because he always wanted to be creating. He often said that once a person ceased to create, he ceased to live. He was by no means a master artist. He did have numerous art books in his possession that he studied. He admired the style and work of various art periods and of specific artists, such as Levitan, Vasnetsov, and Trubetskoi.

In 1953, in conjunction with an expansion of activities planned by the local arts group, Zuckerberg offered a course in beginning sculpture. Six students enrolled. Three years later, in September of 1956, Zuckerberg held one of several sculpture and painting exhibitions in his home. The collection was comprised of some of Zuckerberg’s own works as well as nineteenth and twentieth century Russian artists. The collection included clay, woodcuts, stone, and hammered metal. Zuckerberg acted as guide and instructor to his numerous visitors.

At some point in his life, probably in Russia, Zuckerberg came under the influence of Leo Tolstoy’s teachings. Zuckerberg had been a member of the Russian intelligentsia, and during the revolution it was his philosophy that gave him the inner strength and ability to endure it.

Zuckerberg’s approach to life was a conscious striving for simplicity. Out of choice he dressed in simple, home-made clothes, ate basic foods, and maintained a controlled environment of frugality on his island. It was his desire to be totally self-reliant and capable of meeting all his own needs. This ideal was taken to such an extreme that Zuckerberg abhorred using other people’s labour, except when necessity demanded it.

Zuckerberg nurtured a great love for life. He wanted to experience as much as was possible for him. Simple things like getting up early to see the sunrise, familiarising himself with the majesty of the heavens, enjoying the perfection of mathematics, or creating satisfying works of art were all part of his being. His philosophy on life is best illustrated by an experience he had in Kansas City, while returning from a 1958 trip to Mexico. Two men approached Zuckerberg as he was waiting at a bus depot. The men involved him in a phoney quarrel over lost money. They finished by conning Zuckerberg out of $300 in travellers’ cheques. Zuckerberg’s concluding comment on the affair was, ‘I decided that is was not wise to try and get the money, but to save my life … I am very glad that all went so lucky for me. And the money? The money is for us, not we for money.” These aspects of his character were not for his own benefit only. His conscious effort to live his beliefs was itself an effort to live for the benefit of his fellow man. The realisation of these ideals gained him considerable eminence and admiration in the community.

He felt that the responsibility and obligation of the learned was to teach the unlearned. He sought to bring cultural achievement to the people. Not a political man, Zuckerberg nevertheless used politics with great facility when a wrong needed righting. He was a selfless champion of just causes, and people trusted him. His personality projected confidence, honesty, intelligence, and the strength of inner tranquillity.

Certainly Zuckerberg Island was permeated with the same strong sense. In his island, Zuckerberg found the resources that enabled him to pursue and accomplish his ideals. Bounded and separated by the Columbia River, Zuckerberg was able to grow sufficient fruit and vegetables to meet his needs. His old orchard is still there, as well as the rock lined gardens for his produce and his favourite flower, the iris. The trees supplied him with shelter, material for artistic expression, provided him with solitude, and an open-air cathedral.

His house was a complex structure. Meshed in its timbers were Zuckerberg’s memories of the proud country in which he was raised. It had many structural parallels with his Russian country home near Velikiye Luki. The need for a home enabled Zuckerberg to independently create and build a house that was wholly his. There was to be nothing superfluous or tasteless in the structure. Each part was handmade from exacting specifications. The house was a harmonious unity. He called the concrete causeway, built in 1955, his memorial and it was a symbol that he was not an island unto himself.

Alicia Zuckerberg had suffered from a series of pinpoint brain haemorrhages, beginning in her early fifties. In February of 1960 she was in a Vancouver hospital for treatment. On Thursday, February 4th, Alexander was called to Vancouver after being informed that Alicia had suffered a stroke. That weekend she suffered a second and fatal stroke. Funeral services were held in Vancouver, followed by cremation. Not long afterwards Zuckerberg began Alicia’s plaster grave monument, which still stands over her grave today. It portrays Alicia in a World War I nurse’s uniform. Neighbours helped Zuckerberg erect the monument of which he was very proud.

Inside of a year, Zuckerberg was in the local hospital suffering from a weak heart. Shortly before his death, he notified one of the nurses that he wished to go home. ‘I need to get my house in order,’ he said. The nurse’s husband and another man walked Zuckerberg home through the deep snow. He had to stop and rest several times. His longest pause was by the stump woman sculpture, just within sight of his beloved house. Once they were inside, all the electric heaters were plugged in and a fire was started in the brick fireplace. Zuckerberg was left alone to arrange his papers and affairs, and to say farewell to his island. A week later, friends pulled Zuckerberg on a toboggan back to the hospital. He died peacefully on the 7th of January 1961.

After all is said and done, a life of communication and change is probably what Zuckerberg wanted. He not only felt a duty and an obligation to his fellow man; he truly loved them. Interaction and exchange with people was a delightful pleasure and a challenge. Those who knew him, speak of his readiness for laughter and the constant knowing twinkle of his eyes. Life to him was an exuberant joy, a thing to be taken hold of, and experienced fully in every way possible. No facet of living was to be left untested or considered beyond reach. Once a person said, ‘I will not try, I cannot do this,’ he ceased to live. Zuckerberg never admitted defeat. He lived his life and seemed content.